In the sense in which I use the term, modern design or architecture is not a form or a motif, but an instinct, or rather, a tendency. This tendency or instinct is a fundamental one, like our tendency for good or bad; – or our tendency for beautiful or ugly.

Monthly Archives: March 2012

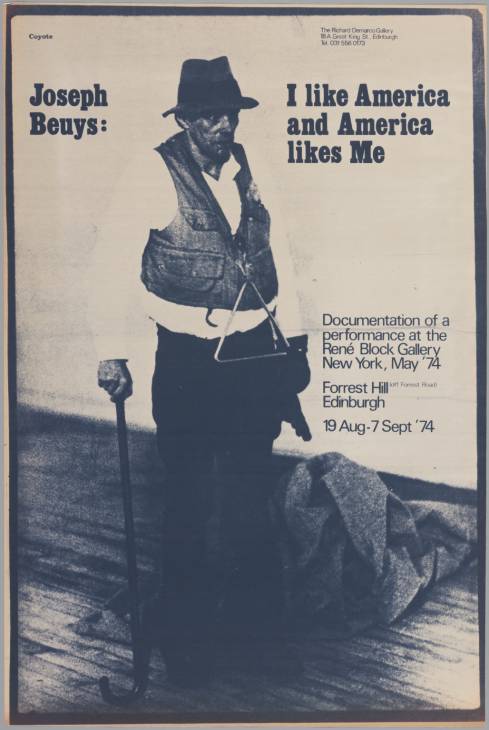

I like America and America likes Me

In this paper I would like to discuss how the post-Vietnam performance, Coyote: I Like America and America Likes Me (1974), was an attempt to clarify his trauma and the culture of German nationalism and Nazis. His staged journey from Germany to the United States in 1974 was a crucial moment in opening up a search for post-fascist aesthetics in dialogue with other species and other nations. Beuys had been invited several times to show his work in the USA, but had publicly announced that he refused to enter the USA as long as the Vietnam War was on. His arrival right after the Vietnam War was an art performance which can be seen as a mythic/romantic anti-salute to US imperialism.

Beuys arrived as the main character in an art performance, which he carefully staged from his moment of arrival in John F. Kennedy airport until his departure one week later. Upon arrival in JFK, his motionless body was wrapped up in a felt blanket (notice the reference to his legendary crash) and placed on a hospital stretcher. He was carried into an ambulance and transported to René Block gallery, downtown New York City. Beuys spent his journey inside the gallery in the company of a coyote and he traveled back to Germany, first inside the ambulance to JFK, right after the performance.

The Lives of Imaginary Others

Re-reading a once favourite book is potentially a perilous encounter. Revisiting those texts that once transfixed us requires a certain audacity. A different response is guaranteed, more pronounced by the passage of time and breadth of life. Reading is transformative, and we re-read through the filter of every other book we have part-remembered; all we can hope for, when we read, is a partial memory. In her book on re-reading Patricia Meyer Spacks writes:

Reading something for the first time may also evoke past selves, inasmuch as we recall bygone experience, of books and of life outside books, when vicariously experiencing the lives of imaginary others. Rereading brings us more sharply in contact with how we-like the books we reread-have both changed and remained the same. Books help constitute our identity.They also, as we reread them, measure identity’s changes with the passage of time.

Those ‘lives of imaginary others’ may be incorporeal, but, if the writer is a good one, can be more substantial than those we come into contact with in real life. Though I forgot her name, Virginia Markowitz (“Virgin for short, but not for long, ha, ha.”), from the automobile casualty insurance company that gave Bob Slocum his first job, is an old acquaintance, first met over twenty years ago when I first read Joseph Heller’s Something Happened.

Joe Heller is a great writer. I agree with John that Something Happened is a significantly better book than the extraordinary Catch-22. In Something Happened, Heller restricts himself to streaming the narrative through Bob Slocum. Heller says:

There is very little in Something Happened. Bob Slocum tends to consider people in terms of one dimension; his tendency is to think of people, even those very close to him—his wife, daughter, and son and those he works for—as having a single aspect, a single use. When they present more than that dimension, he has difficulty in coping with them. Slocum is not interested in how people look, or how rooms are decorated, or what flowers are around.

Even presented in one dimension, Virginia, ‘that pert and witty older girl of twenty-one’ is as potent a force as when I first read Something Happened, though, on this reading, she is more tragic than erotic. Though Virginia’s life is imaginary, my memory of her is strong, equally for the ‘limited persona’ of Bob Slocum and his dysfunctional family.

I’m only 143 pages into this 569 page edition and enjoying it mightily. Jhumpa Lahiri’s wonderful remark: “Rereading them, certain sentences are what greet me as familiars” is so true of Something Happened. One small sample:

In my department, there are six people who are afraid of me, one small secretary who is afraid of all of us. I have one other person working for me who is not afraid of anyone, not even me, and I would fire him quickly, but I’m afraid of him.

There are several novels that come to mind that capture the dissonant chords of marriage and family life, far fewer that encapsulate the banality and quiet awfulness of office life. Heller nails both with precision.

Yves Tanguy’s Gentle Art

Thomas B. Hess: “I knew Tanguy toward the end of his life; he was a witty, laughing, friendly man; he loved his drinks and bird call records […] Tanguy’s gentle art began aloof; it ended with requiems in which nostalgia and sentimentality are regulated to the artist’s obsession with the elegant little world he invented and then painfully, stoically, extinguished.”

Thinking the Twentieth Century by Tony Judt

Unavoidable, while reading and thinking about this book, is the mental picture of Tony Judt paralysed with ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), a dire disease that paralyses the body but leaves the mind intact. In this state, worsening as Timothy Snyder and he finished the book, Judt “talked” the twentieth century.

Structured around a series of long conversations between Snyder and Judt, the book is an intellectual autobiography that begins with Judt’s early (lapsed) Zionism and Jewish trauma in Europe, and progresses through European intellectual history before and after Judt’s birth in 1948. The book ends with a brief but rigorous analysis of the failure of American politics towards the end of the twentieth century and beyond.

Whether or not one agrees with Judt’s opinionated meditation on Europe’s intellectual history in the twentieth century, the book offers much to think about. His detailed examination of Eastern Europe, in particular the failure of the West to understand so much about the region and its nuances, is enlightening and leaves me with a yearning to fill the gaps in my comprehension. I sincerely recommend Thinking the Twentieth Century, both as an intellectual autobiography and an eloquent, rich European history of ideas.