Dostoevsky’s novels, wrote John Bayley, “are full of a stifling smell of living and littered with constitute daily reality,” as compared to Tolstoy who has, “houses and dinners and landscapes, ” which is a striking and nicely balanced comparison.

There is a singular scene in Anna Karenina which marked my transition from curiosity to a genuine fondness for Tolstoy’s story. The noble Levin scythes hay with the peasantry, transitioning over the course of the long day from a sense of detachment and to a more instinctual rhythm. It is a similar metaphor to Hamlet’s “the interim” as the place where contentment is found. As Tolstoy wrote elsewhere, “True life is not lived where great external changes take place.” It is a quite extraordinary scene and set my decision to read more Tolstoy, particularly War and Peace.

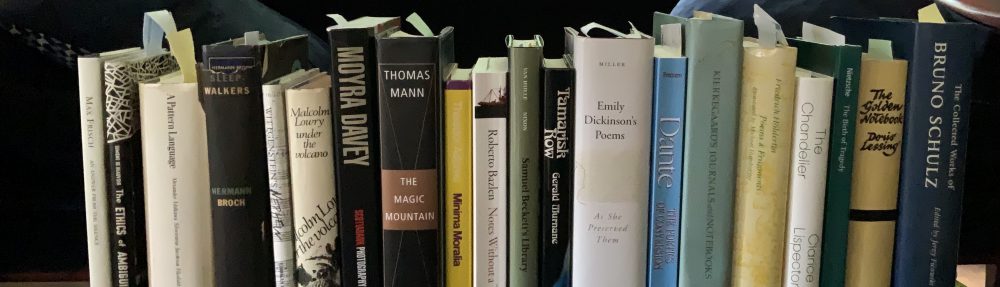

Normally at this time of the year I am brimming with plans for next year’s reading, but apart from wishing to read through those Shakespeare plays I’ve not read and more of Samuel Johnson’s Lives, I have few other settled intentions. “Age with his stealing steps / Hath clawed me in his clutch.” As I turn fifty-nine a deep sense of mortality is shaping what I read and I find myself turning more to those works of art that have eluded me to date. There is more urgency to try to read well. I read more books (87) this year than any other but feel that I read too much. With a handful of exceptions, the most profound and interesting reading this year was all older books.

Time’s Flow Stemmed feels a little rudderless at the moment but still appears to be of some interest if judged by 1,200 subscribers and 1,800 visitors per month on average, but I have no point of comparison. If any readers would like me to respond to specific questions about my reading life please either leave a comment or send an email. I still clearly feel a need to write into the internet as manifested by the occasional post here and my sporadic social media presence.