“The answer is contained in the one feature unifying the four passions [walking, swimming, writing and reading] to which I’ve just dedicated, respectively the last four ‘paragraphs’: namely, a fifth passion, situated as it were behind the four others, like the sign or figure of their kinship: the passion for solitude.”

“The answer is contained in the one feature unifying the four passions [walking, swimming, writing and reading] to which I’ve just dedicated, respectively the last four ‘paragraphs’: namely, a fifth passion, situated as it were behind the four others, like the sign or figure of their kinship: the passion for solitude.”

If writing is cathartic, it is as much about the sharing of pain with others, and a necessity to publicly acknowledge loss, rather than deal with uncomfortable silences, that compel the therapeutic need to express grief in concrete form. Writing provides a way to transcend the ordinary dialogue of mourning with its codes and conventions. In his The Great Fire of London, the death of Jacques Roubaud’s wife and the inevitable ending of his parents’ lives are meditated through his memories of them and their shared and past existence. The book is a prolonged beginning (Roubaud uses the term branch) of a much more extensive project, controlled through an elaborate set of textual devices informed in part by his love of mathematics.

Reading Roubaud’s novel is a vertiginous experience, occasionally feeling that one is making no less an effort than the writer during its creation. Through an unusual deployment of interpolations and bifurcations, Roubaud sits between two mirrors that face each other to explore the nature of memory and writing. As the one who is simultaneously the narrated, the narrator and writer, Roubaud explores similar terrain to Coetzee, who described a similar intention, “finding one’s way into the voice that speaks from the page, the voice of the Other, and inhabiting that voice, so that you speak to yourself . . . from outside yourself.” Roubaud carefully layers his elliptical portrait, but like many who are solitary by instinct, reticence is part of his style.

There is mourning and regret in The Great Fire of London, but this is not a melancholic or elegiac book. The short, numbered fragments that make up each of the six chapters can be read in linear fashion, or by drifting back and forth between each relevant interpolation and bifurcation. These elements don’t feel like capricious interruptions, but serve to explore aspects of perception and contemplation. The recondite and difficult fifth chapter begins with the suggestion that it “can be omitted during a first reading”, which, with hindsight, is advice that should be taken if a reader is to arrive at the final chapter with sufficient energy.

I had no intention to write about The Great Fire of London. If any book deserves a second reading, it is this solemnly beautiful book, but, after a haunted night filled with the imagery and atmosphere of this novel, it dawned on me that I am compelled to write about it in order to unburden my first reading experience.

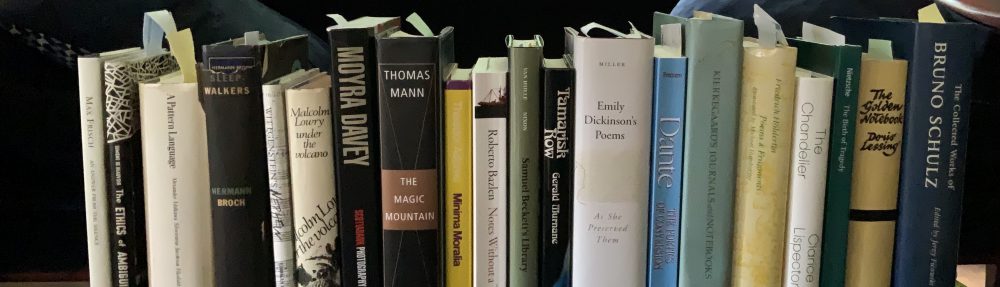

Roubaud’s The Great Fire of London sits on the shelf next to its two sequels. There are six branches to the now completed Project, the last of which in the edition above, branch five of the Project, entitled La Bibliothèque de Warburg, is unlikely to be translated into English anytime soon, so my creaking French must suffice to allow me to explore that remarkable library that I find so fascinating. I will also reread Alix Cleo Roubaud’s Journal, last read seven years ago.

Sometimes it seems daunting just how many books there are yet to read—possible treasures that we may never make time for— one discovers a book like The Great Fire of London, which serves as a reminder of the scarcity of books that can open us up to an edenic and intense quietness, an experience that disrupts our quotidian view of the world. The treasure-trove of such books is small, and the gap between their uncovering seems to widen in proportion to age, which at least makes a reading life less overwhelming.

Thank for writing about this – I’ve been intrigued by your tweets and will keep this on my radar. It is daunting how many books there are to be out there, but the prospect of an unexpected discovery of something wonderful does keep me reading.

My pleasure, K. There’s a long year ahead, but I shall be amazed if this isn’t one of the best books I read in any year. I’m already looking forward to re-reading.

In part, b/c of your Twitter post, I began rereading GFL. (Read these books Branches One through Three (and a half) in 2018 and filled a notebook with my reading notes.) I guess it will be many years before the other branches are translated into English, so I’ve ordered the French originals and will be embarking on a slow read. It enriches the reading experience to have fellow travelers (even if only for the three volumes translated into English).

My single 2000-page French edition arrived this week, impatient as I was to do my best with the sixth branch, which feeds my near-obsession with Aby Warburg’s Bilderatlas Mnemosyne and library.

Single edition? Only 2000 pages? Curious to know if that edition has the multicolor text for La Dissolution.

This edition only goes up to La Bibliothèque de Warburg, but includes the later Impératif catégorique (Branch 3, Part 2, of the Project). It doesn’t include La Dissolution. I read somewhere, though I can’t find the reference—perhaps I dream it—that there is some symbolism behind a 2000 page edition.

Out of curiosity, what’s the French title for this omnibus edition of branches one through five?

The title is ‘le grand incense de Londres’, with the first branch called La Destruction.

Ah, okay. I now see the one published in 2009 by Seuil is what you’re talking about. I was only finding the 1989 publication which (obviously) wouldn’t be the omnibus. Thanks.