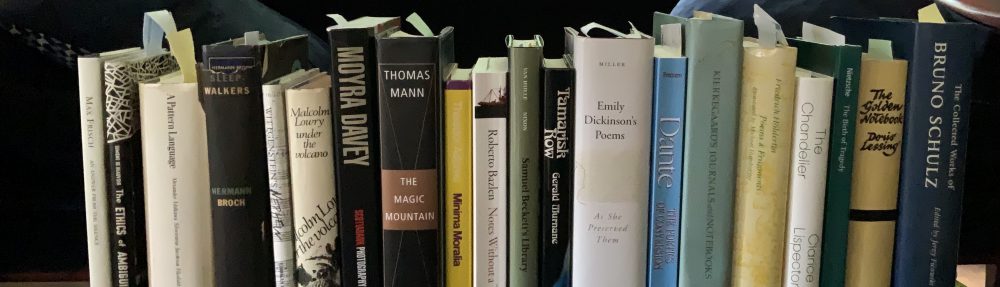

Ambitious readers must, despite carefully acquired insouciance, weigh up their stacks of dusty unread books with the time available before they return to dust themselves. They have surely roughly calculated a number, assuming an average lifespan and being blessed with continued cognitive faculties. It is quite possible that their groaning shelves are already a display of ambition over cold certainty, even without including in the calculation the additional volumes that will surely be acquired, surreptitiously, or with resigned and solemn endurance. Umberto Eco, with a library split over two homes, owned a total of fifty thousands books, necessary he deemed as a research library: “I don’t go to the bookshelves to choose a book to read. I go to the bookshelves to pick up a book I know I need in that moment.”

With non-fiction, deciding what to read is sometimes a reflection of a passing or enduring interest, perhaps in Kabbalah, or human brain evolution, or the Punic wars, often stimulated by something read in a novel or poem, something not quite understood. “Not understanding”, wrote Enrique Vila-Matas, can be “a door swinging open.”Non-fiction is often of the moment, requiring some fresh context and matures less well than poetry or fiction, unless tracing a line of thought through a particular discipline; an exception being theology or philosophy where the peak may well be behind us. Fiction and poetry are usually improved with a patina of age and time.

Poetry is more personal, arising from just the right admixture of form and subject matter, an integrity dedicated to what George Oppen described as “a determination to find the image, the thing encountered, the thing seen each day whose meaning has become the meaning and the colour of our lives.” I chose poets as carefully as I decide what to eat each day, certainly for aesthetic bliss, but also for fascination with the language and thoughts of others. Few intellectual exercises can be more invigorating that to watch the working of another human mind. In some senses, poetry and novels are the only way to see another person from within.

Fiction I choose with equal care, discarding occasionally those novels that, as Jenny Erpenbeck described, fail to “open a door for me into my own reflections.” Peter Schwenger wrote, “When narrative works, when a text is felt, it produces that complex metabolic reaction in us that we call a work’s ‘effect'” It might be that after a time, all is left of a novel in our memory is an atmosphere, or story-line, but as Jenny Erpenbeck wrote, “the most important things sink deeper in our memories, we internalise them, take them into our bodies, and they stay there, blind and mute.” We readers are minds inspired by the books we choose.

Often the books that make the deepest impression, slipping deeply into us with barely a sound, are not those expected to become, to borrow a term from Nietzsche, our divine lizards. There were other attempts over the years to read Gerald Murnane, at least three, but this year with Tamarisk Row I crossed the threshold to discover what might be the only living English language writer both advancing the form and doing something beautiful. With Invisible Yet Enduring Lilacs and even more so with A Million Windows I found, against all expectations, a living writer that could slake my thirst for a sustained glance into a mind so very different to my own. Murnane writes as he does from necessity. His inimitable prose does not suffer the superfluous, stylistic postures that tarnish much of twenty-first century English language fiction. His vision is singular and haunts my thinking to the point that I see the world a little bit differently after reading these books. That is all I ask from fiction (and poetry).

This sense of writing that touches the bases of life is how I emerged from reading Jeremy Cooper’s Ash Before Oak. I persisted past the perception that this was the diary of a solitary man living remotely, something like Roger Deakin’s Notes From Walnut Tree Farm, not a form or theme I dislike when I feel like vicarious escape, but something darker and more raw, closer to V. S. Naipaul’s The Enigma of Arrival. Unlike Murnane’s writing that compels me to read every word he wrote, I feel no urge to find out more about Cooper or his work, merely content to spend time with his book that captures so well the unsettling nature of an arrival coloured by memory. It might not add anything to literature, but it opened up a space for peace and contemplation.

This was a year when I read a lot more poetry: Auden, Larkin, that kind of thing, but it is Natalie Diaz’s collection in Postcolonial Love Poem that I read and kept on my study desk to reread almost daily. Diaz deals in elaborate symbolic imagery, but the writing is both exuberantly beautiful and concrete, reflecting not only her lived experience, but an intelligent portrayal of the human condition. She took me into alien realms and stimulated in no small way a transformed view of reality. I’m looking forward to reading her first collection, When My Brother Was an Aztec.

The essays in Jenny Erpenbeck’s Not a Novel: Collected Writings and Reflections are uneven and, as is the nature with a collected edition, repeat themselves a little, but this is nevertheless an insightful series of essays on her early life in East Germany—a place of rich and near endless fascination—and her experience of writing and reading. Erpenbeck comes across in her novels as a deeply serious writer of poetic and ethical integrity. These essays enrich the reading of her novels to the point I intend to reread them all chronologically after another reading of the pertinent essays.

It is unusual that I read more non-fiction and poetry than novels, but no real surprise in this uncommon year when I read nothing for five weeks, listening only to music for artistic sustenance. Peter Schwenger’s At the Borders of Sleep is an unconventional work of literary criticism. It addresses Borges’s statement that “literature is nothing more than a guided dream”. My experience of reading the book was sufficiently intense to trigger a hypnagogic vision during that liminal stage between being awake and falling off to sleep. It was also a reminder of the radical mystery of literature and its affects. It brought to mind a sentence of Gerald Murnane’s, “When he paused from following the text, or even when one or another book was far from his reach, even then he had access not only to narrated scenes and events but also to a far more extensive, fictional space, so to call it.”

However wretched this year has been, to finally have in my possession Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, his encyclopaedic collection of images collected to tell a story of how ideas and rituals persist over time, and how we humans fit into a cosmic context, is genuinely thrilling, a memorable event against a bleak backdrop. Georges Didi-Huberman’s Atlas, or the Anxious Gay Science not only provided a brilliant pathway into the Atlas, but gave me space to reflect on the interrelationship between philosophical thought and art history.

Beyond a contemplation of the books I read this year that left the deepest imprint, what is this post that has rambled on far too long? What am I? Am I a blogger again? I’ve no idea. I’ve written more this year than any other, mostly in my notebooks, but felt an need to write into the internet again.If you’ve read this far, please accept my thanks and wishes that the year ahead proves far less interesting than this year.

Thank you so much for this amazing post, Anthony! Yes, let’s wish for a far less interesting year!

Dear Anthony,

This reading has been one of the most pleasurable presents I have received this time of the year. I hope you keep on writing and posting. Mis mejores deseos.

Thank you!

Really hope you will continue writing for us (your almost anonymous, silent & invisible – but still very appreciative blog gang 😉)

ps: I cannot remember how I came to read «When My Brother Was an Aztec», but I do remember it as an extraordinary book of poems …

Thanks, Sigrun, your appreciation is much appreciated! I rarely discover a contemporary poet that speaks to me, so looking forward to seeing Diaz’s first book, and what may come in the future.

Delighted to see you here again and read these reflections and suggestions, Anthony. I published my own year-end reading comments and list today, too. I read Murnane’s “The Plains” several years ago, and though I finished it, I left the book feeling bemused and not really satisfied that I had fully understood what he was doing. On the strength of your comments here, I’ll try again with “Tamarisk Row.” Also, I’ll get Diaz’s collection. Thanks. (And please keep writing here, I miss your posts!)

Hi Beth. I read your post earlier with much pleasure and will respond in comments soon. I tried starting with “The Plains”, but “Tamarisk Row” gives a better grounding I think. And thank you for your delight. It means a lot.

Very good to see you back, Anthony. I enjoy your extended literary reflections. Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas looks fascinating. I’m curious to read more of your reactions to it. Regarding reading and consciousness, and semi-consciousness, I often find that reading late at night results in the hypnogogic development of a book into realms that the author hasn’t actually committed to paper. It’s an interesting area of the mind that has quite a different weight than the interesting developments to which we are subjected in waking life. Looking forward to more of your writings here. All good wishes for the ever-opening and unpredictable future.

Thanks, Des.Very best wishes for the new year.

I see I am not the first to welcome you back – but welcome back, if “back” is where you are. Thusfar the only Murnane I’ve gotten to is “Stream Systems,” which certainly does stick in the teeth of one’s reading mind, as it were. I love how he’s constantly “doing philosophy” in his work without the jargon and the redundancy, and I love how his fictions, so coolly obsessive, hunt down the idea of meaning without bothering to explain what they’re doing. And reading him does disarrange whatever one thought “style” ought to be.

Thanks. I’ve enjoyed the two days spent writing this post, and pushed the Publish button after two hours of agonising, so, yes, back, in some form at least.

So glad to see you back Anthony, and I hope to be able to read more of your thoughts when you feel like sharing them. These times are far too interesting for me, and I have been hanging on to books as a survival mechanism. Much of what you say resonates, particularly the fact that I now own more books than I will ever be able to read. But I take comfort in the fact that like Eco, if I want to read a particular book or type of work I will probably have the right thing to hand. I have found myself very drawn to non-fiction this year and quite selective about the fiction I engage with. Whether that will continue into 2021 I’m not sure, but it will be interesting to see! May the year bring you many bookish blessings!

Thank you. From week to week I veer between filling what seem to me gaps in my library, to wondering how many of my books I shall leave unread. I’ve long had a policy of reading the prelude/intro or first few pages of every book I acquire, so none can be said to be truly unread and each gets a chance to be ‘engrafted in the tenderness of thought’ and become necessary of immediate attention. Very best wishes for the new year.

What a wonderful way to write an end-of-year roundup, Anthony! I just wrote mine, but it was much more prosaic. Your recommendation of Gerald Murnane was so convincing that I’ve just ordered a copy of Tamarisk Row. I could do with a divine lizard of my own right now. Happy New Year!

Thanks, Andrew!

So wonderful to see you writing here again!

Thanks, A! I’m enjoying writing here, so pleased that you are still reading.

Pingback: Divine Lizards: A Year of Reading – playing footsie with another dimension