Dostoevsky’s novels, wrote John Bayley, “are full of a stifling smell of living and littered with constitute daily reality,” as compared to Tolstoy who has, “houses and dinners and landscapes, ” which is a striking and nicely balanced comparison.

There is a singular scene in Anna Karenina which marked my transition from curiosity to a genuine fondness for Tolstoy’s story. The noble Levin scythes hay with the peasantry, transitioning over the course of the long day from a sense of detachment and to a more instinctual rhythm. It is a similar metaphor to Hamlet’s “the interim” as the place where contentment is found. As Tolstoy wrote elsewhere, “True life is not lived where great external changes take place.” It is a quite extraordinary scene and set my decision to read more Tolstoy, particularly War and Peace.

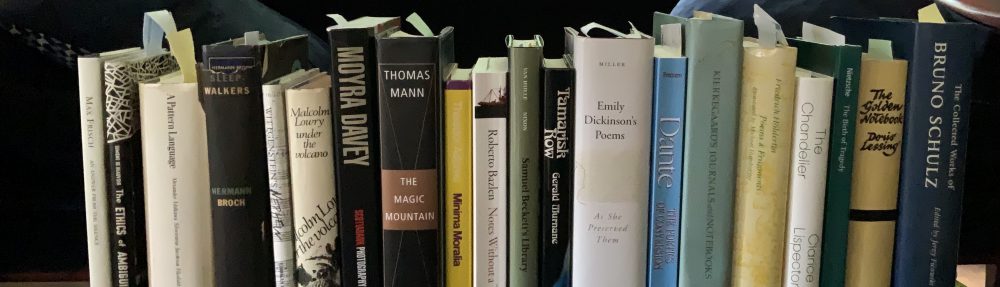

Normally at this time of the year I am brimming with plans for next year’s reading, but apart from wishing to read through those Shakespeare plays I’ve not read and more of Samuel Johnson’s Lives, I have few other settled intentions. “Age with his stealing steps / Hath clawed me in his clutch.” As I turn fifty-nine a deep sense of mortality is shaping what I read and I find myself turning more to those works of art that have eluded me to date. There is more urgency to try to read well. I read more books (87) this year than any other but feel that I read too much. With a handful of exceptions, the most profound and interesting reading this year was all older books.

Time’s Flow Stemmed feels a little rudderless at the moment but still appears to be of some interest if judged by 1,200 subscribers and 1,800 visitors per month on average, but I have no point of comparison. If any readers would like me to respond to specific questions about my reading life please either leave a comment or send an email. I still clearly feel a need to write into the internet as manifested by the occasional post here and my sporadic social media presence.

“The constant, fundamental underlying urge is surely to live more, to live a larger life.”

“The constant, fundamental underlying urge is surely to live more, to live a larger life.”