The voice remains. It somehow survives that cataclysmic leap from oral epic to self-consciousness fiction. The inimical voice of writers like Beckett, Woolf and Bernhard. This isn’t the first year I read Jon Fosse’s writing, but it is the first in which his voice became a tremendous presence.

I’ve read most of Fosse’s books available in English translation, saving Trilogy, and his writing seems to have that rare transcending quality called literature. In his essay, Anagoge Fosse writes, “Why do we never read with our attention turned towards the thing in literature which makes it so obvious that it both belongs to the world and does not belong to the world? That makes it incomprehensibly comprehensible? Which gives it meaning without meaning? Why don’t we read to see how the paradox of literature is a strange fusion of the extremely heavy and the extremely light, of the material and the spiritual?”

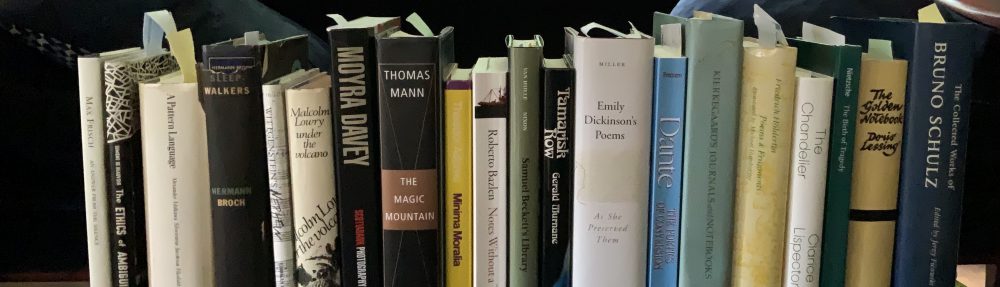

My most cherished literary discoveries encapsulate literature in precisely those terms: writers like Mayröcker, Llansol, Lispector and Murnane. This year, Fosse’s Septology, translated by Damion Searls and Melancholia II, translated by Eric Dickens, left the most significant impression, together with Thomas Bernhard’s Yes, translated by Ewald Osers and Friederike Mayröcker’s brutt, or The Sighing Gardens, translated by Roslyn Theobald.

Much of the summer was spent with Geoffrey Hill’s Broken Hierarchies: Poems 1952-2012. A planned chronological reading ended up with the repeated rereading of Tenebrae and For the Unfallen: Poems 1952-1958 before getting entangled, against my usual practice, with explicatory secondary texts. Hill is a highly lucid poet, particularly in his early days. These are poems to get to know throughout a lifetime, but the scholars help to build light.

For a few months, I carefully followed Iain McGilchrist’s prose in The Matter With Things, a book I shall undoubtedly reread, enhanced by my later reading of Geoffrey Hill and Jon Fosse. Perhaps these coincidents only seem so; the future’s roots are buried in the past.

Also notable this year was one of Steve Mitchelmore’s favourites of last year: Ellis Sharp’s mesmerising Twenty-Twenty, which records daily for a year his struggle against the compulsion to write and a return to Beckett’s Company, a reminder to slow down and look back more often.