I bear no guilt for reading fewer books this year than any other in recent memory – I regret only my morbid fascination with the sulphurous news, as the worst aspects of human nature become manifest. My natural refuge in literature has proved insufficient distraction to the horrifying potency of watching vultures tearing at a creature’s entrails, gripped and subdued by the grisly pantomime. I don’t wish to drown in the spectacle. I must find balance and some self-discipline, though only imagine that this year is merely grisly prelude to further gross stupidity and narcissism next year.

It is Jorge Semprún’s writing that proved most alluring this year. In writing Literature or Life, he chose to end a “long cure of aphasia, of voluntary amnesia” to write this lightly fictionalised memoir, controlling and channeling his complex memories of the evil exerted during his incarceration in Buchenwald. I read backwards to the lyrical reticence of The Long Voyage, an almost dispassionate account of the cattle train journey to the concentration camp”. Semprún reassures that it is possible to both write poetically and read about barbarism. Literature or Life is one of those books that sit on one’s shelves for years before one is compelled to read even a sentence. The image that lingers most intensely from Literature or Life is his consideration of which books to take on a return to Buchenwald to film a documentary about the camp. In the end he opts for Mann’s The Beloved Returns and a volume of Celan, who perhaps has written the greatest poems about the Holocaust. Semprún quotes a verse from Celan, “hoping, today/ for a thinking man’s/ future word/ in my heart.”

Another book that languished unread on my shelves was a fine first edition of Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai. Greatness resides in this wonderfully singular story of a mother and son obsessed with Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai. I was swept helplessly along by the the torrent of DeWitt’s thought who brings into her novel not only Kurosawa but Ptolemaic Alexandria, Ancient Greek and Fourier analysis. There is a curious quality to the work –stark, lonely, even sadistic– it is one of the most original novels of our time, original as regards sensibility.

I discovered Max Frisch’s work this year. Frisch’s novels offer up a world where no-one is allowed to rest easy; self is thrown back upon uneasy self. There is no escape. Not that Frisch is without hope; his novels unfold the twisted and often darkly comic search for a way out. It is Homo Faber that made the deepest impression, its melancholy cadences contrasting with the ice burn revelation of an incestuous relationship with his daughter.

This year also gave me Anna Kavan’s haunting imagery. The stories in Julie and the Bazooka and I am Lazarus read like a heightened version of Burroughs’s fantasies. Kavan can be gruesomely funny, but with a richness that lies in her proximity to the sensory and the unconscious. It is the chilling tales of narcosis wards that remain, months after reading these stories, the struggle to awaken from speechless unconsciousness. Kavan’s writing, though piercingly clear, is best taken in small doses for its horror and loneliness weighs numbly on the heart.

I’ve read Christopher Logue’s Homer in part during its long evolution but War Music collects all the parts of his adaption of the Iliad into a single edition. This is Homer channelled through Logue’s erudition and the jarring of modern technology. It is a creative ‘translation that shouldn’t work but Logue invigorates an epic that always appears modern.

As the year approaches its end, Reiner Stach’s Kafka: The Early Years is casting a very strong spell over me, This first volume is the last of three to be published due to an overhanging lawsuit. Auden wrote, “Biographies of writers are always superfluous and usually in bad taste”, but there are a few brilliant, definitive biographies that count as essential. This and Stach’s companion piece Is that Kafka? restore Kafka from cliché so we might return to his writing anew.

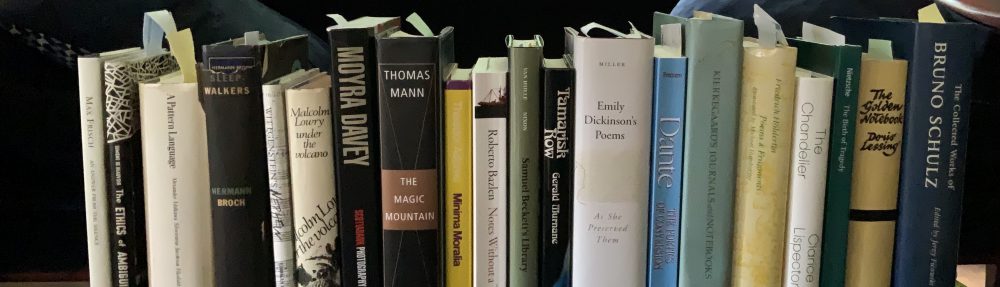

Here is a list of the 55 books I’ve read so far this year.