There was a time when I drifted between reading books of poetry and fiction without a thought for the writer; choosing what to read next— there was no enduringly impatient stack—was a function of where the endlessly reflective waves induced by the last book led me, or more prosaically, whatever caught my attention when browsing in my nearest bookshop.

Around my early twenties, a different whole seemed to fall into shape and I begun to pay attention to certain writers and, setting a pattern that has followed throughout my reading life, to read them to completion, seeing the inevitable minor works as a pathway to answering the thousand questions that arose around the major books.

Once I drew up a list of best books, what I termed a personal canon, but this would prove a shot-silk, a slippery list that refused stability. What, after all, is best? The Canon? Or those books that once read refused to be forgotten, crystal-carbon in memory? What of those evanescent books thought of as favourites, where little lingers beyond perhaps an atmosphere, or a single character?

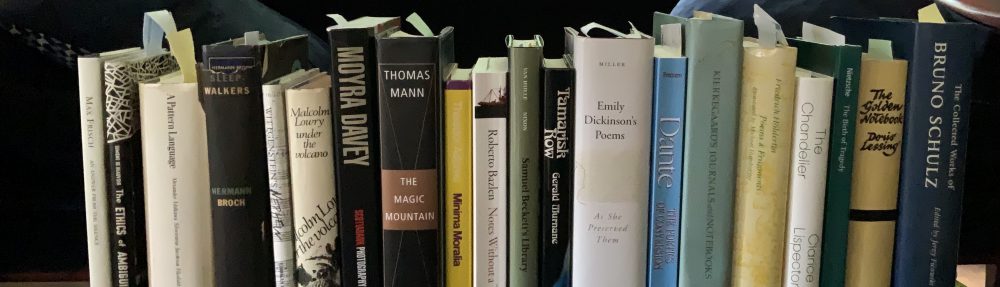

Instead, in what I optimistically term my maturity, I choose writers over specific books, and my choices embody what Anthony Rudolf in Silent Conversations terms: “magical thinking, talismanic identifications and ghostly demarcations”. There is a distinction between those I read that will probably always be read whilst there are literate readers to be found, say Samuel Beckett, Anton Chekhov, Franz Kafka, Virginia Woolf, Emily Dickinson, James Joyce and Charles Baudelaire.

There are those I read closely because I am, for reasons not always fully understand, intrigued by the way they think or observe the world, for example Peter Handke, Gerald Murnane, Dorothy Richardson, George Oppen, Clarice Lispector, Christa Wolf, Mircea Cărtărescu and Enrique Vila-Matas. Time and the quick sands of taste will decide whether each find a home in posterity.

There is a far stranger category of writers I have only sampled, yet fascinate me deeply: Maurice Blanchot, Ricardo Piglia, Marguerite Duras, Hans Blumenberg, Laura Riding, Arno Schmidt are all examples, but I could name a dozen others. These interest me as much for the lived life as the work, though I always plan to explore the latter more deeply.

Reading books becomes a way to find the writer, or at least to see a glimpse of that writer’s mind. In doing so, I find that I am a part of all that I have read, that reading is a process to becoming. The more I contemplate the act of reading and of what I read, the stranger it seems. I understand less than I did when I began. Where once writing seemed certain and assured, as I moved toward the depthless prose of the writers that I came to consider part of my pantheon, the more I felt strangely included in that writer’s thought process.